Marduk was the principal god of the city of Babylon, the rise of his cult to importance being intimately related to the rise of Babylon from a small city-state to the capital of a regional empire. Marduk’s central cult place was the temple known as Esagil in Babylon, where Marduk was worshipped alongside his consort Sarpanitu (although, occasionally, the goddess Nanaya was recognised as the god’s wife).

Marduk was the principal god of the city of Babylon, the rise of his cult to importance being intimately related to the rise of Babylon from a small city-state to the capital of a regional empire. Marduk’s central cult place was the temple known as Esagil in Babylon, where Marduk was worshipped alongside his consort Sarpanitu (although, occasionally, the goddess Nanaya was recognised as the god’s wife).

Marduk’s origins are clouded in obscurity. His worship is attested, however, as early as the Early Dynastic Period and his position as Babylonian chief deity in evidence from at least the Third Dynasty of Ur. Marduk seems early on to have absorbed the identity of a deity local to the Eridu region, Asarluhi, a son of the god Enki; as a result, Marduk became regarded as the son of Enki / Ea. A much later mythological development surrounding Marduk was the gradual recognition of Nabu, god of wisdom and deity of nearby Borsippa, as the son of Marduk.

The conventional writing of the name of Marduk with the cuneiform signs literally meaning “bull-calf of the sun” probably reflects a popular etymology. With the god’s rise to supreme importance, he was often simply referred to as “Bel” (meaning ‘Lord’).

The increasing emphasis on the cult of Marduk as state-god under the Babylonians has been compared favourably with monotheism, though the god’s worship apparently never led to the denial of other deities’ existence, nor the rejection of female deities.

The symbol of Marduk is a triangular-shaped spade or hoe, known as the marru, and may reflect Marduk’s origin as a local Babylonian agricultural deity.

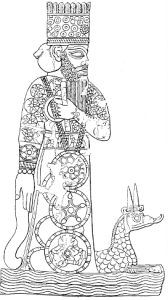

The animal of Marduk (shared with Nabu), the snake-dragon or mušhuššu, was apparently usurped from the local deity of Ešnunna, Tišpak, sometime soon after that city’s conquest by the armies of Hammurabi of Babylon. The snake-dragon was a true composite beast, consisting of a scaly body, a serpent’s head, the horns of a viper, feline / leonine front feet, the hind feet of a taloned bird and a scorpion’s tail.

(top right) The god Marduk and his mušhuššu – detail from a large lapis lazuli cylinder dedicated to the deity by the Babylonian ruler Marduk-zakir-šumi I (c. 854-819 BCE). As revealed by the accompanying inscription, the inscribed cylinder was to be set in gold and hung about the neck of the cult image of Marduk in Esagil, the primary temple of the god in Babylon.The cylinder was discovered in Babylon, at the Parthian period house of a bead-maker.

Snake-Dragon of Marduk, c. 604-562 B.C.; Mesopotamian, Neo-Babylonian Period; Ishtar Gate, Babylon; Molded, glazed bricks; 1.2 x 1.7 m (45 1/2 x 65 3/4 in.); Detroit Institute of Art, Founders Society Purchase; 31.25.

Snake-Dragon of Marduk, c. 604-562 B.C.; Mesopotamian, Neo-Babylonian Period; Ishtar Gate, Babylon; Molded, glazed bricks; 1.2 x 1.7 m (45 1/2 x 65 3/4 in.); Detroit Institute of Art, Founders Society Purchase; 31.25.

The striding dragon formed part of thedecoration of one of the gates of Babylon. Nebuchadnezzar, whose name appears in the Bible as the despoiler of Jerusalem (Kings II 24:10-16, 25:8-15), ornamented the monumental entrance gate dedicated to Ishtar, the goddess of love and war, and the processional street leading to it with scores of pacing glazed brick animals: on the gate were alternating tiers of Marduk’s dragons and bulls of the weather god Adad; along the street were the lions sacred to Ishtar. All of this brilliant decoration was designed to create a ceremonial entrance for the king in religious procession on the most important day of the New Year’s Festival.

Select Bibliography

Bottéro, J.

“Les Noms de Marduk, l’écriture et la ‘logique’ en Mésopotamie ancienne”, in Finkelstein Memorial Volume, Hamden, CT, 1977, pp. 5-28.

George, A.R.

“Marduk and the Cult of the Gods of Nippur at Babylon”, Orientalia NS 66 (1997), pp.65-70.

Lambert, W.G.

“Studies in Marduk”, BSOAS 47 (1984), pp.1-9.

Sommerfeld, W.

Der Aufstieg Marduks: Die Stellung Marduks in der babylonischen Religion des zweiten Jahrtausends v. Chr., AOAT 213, Neukirchen-Vluyn, 1982.

I am fascinated by the origins of beliefs. This information is important to anyone who loves history and the truth of how Judaism,Christianity and Islam have borrowed these legends to formulate their own belief systems.